| Home | About Us | Resources | Archive | Free Reports | Market Window |

|

Steve's note: DailyWealth Weekend has a new feature – The Guest Essay. Each weekend, we'll publish an essay by one of the world's best investors.

World traveler, investor, and writer Jim Rogers kicks off the program... Enjoy! Fire in the FieldBy

Saturday, March 4, 2006

When I was a child in the 1950s, my family would drive from Alabama, where we lived, to Oklahoma to visit my grandparents.

I can still remember being amazed to see fires in the fields along the road. No one seemed to care. It was only decades later, as a young man on Wall Street looking around for some investment opportunities, that I learned the reason for those fires along the Oklahoma roads of my childhood.

There were oil fields out there, and in 1956 the Supreme Court had ruled that the government had the right to regulate the price of natural gas. Washington kept natural gas so cheap that it was more economical for those Oklahoma producers to "flare" it—burn it off—than to produce it while pumping oil.

And there was certainly no financial incentive for anyone to look for new sources of gas or oil, for that matter, which was plentiful (and thus inexpensive) in the 1950s and 1960s. Drilling companies went out of business, and exploration dropped off. The same was true for most other commodities—lots of supply, low prices.

By the early 1970s, those prices had begun to rise. Why? Time turns even excess inventories into empty warehouses.

No matter how much of a given commodity there is, if supplies are not maintained on a regular basis they will become depleted, leading to price increases. More and more Americans were driving bigger cars; cold winters still required heating oil; and air-conditioning made it possible for more people to thrive in areas of the nation where the heat and the humidity had once discouraged enterprise.

And then all those stockpiles of natural gas and oil began to disappear—with nothing to replace them, because no one had been able to make a buck in the hydrocarbon business for years. Soon investors were falling over one another in an effort to capitalize on escalating prices.

Between 1966 and 1982, the stock market went nowhere and with double-digit interest rates the bond market collapsed.

Meanwhile, commodities boomed. But high prices soon did their normal work of encouraging new supply while cutting demand. Companies began drilling for oil, opening up new mines, and planting corn and soybeans. Gold plunged from $850 in 1980 to $300 in 1982, sugar went all the way back down to 2.5 cents in 1985 from the 66 cent price reached in 1974, while oil collapsed to less than $10 a barrel in 1986.

And then the cycle began to repeat itself. With supplies of commodities high and prices low, investors looking for value opportunities eventually returned to the stock market in the mid-1980s.

That, too, was predictable: Investors never chase bears. By the 1990s, U.S. investors, mesmerized by the Internet bubble, were funneling every cent they had into company shares of "growth stocks" selling for more than 50 times earnings. In 1999 alone, venture capitalists invested $42 billion—more than the three previous years combined; IPOs raised $68 billion, 40 percent more than any year on record. Not one IPO was for a new sugar plantation, lead mine, or offshore drilling rig, I can assure you.

In the meantime, metals mines and oil and gas fields were becoming depleted.

To me, it was déjà vu. The oversupply of two decades had created low prices that eventually spawned a bull market in commodities—just what happened in the late sixties.

Once again, commodities had been plentiful and cheap. The Asian and Russian crises of 1997 and 1998 led to the final liquidation of those regions' commodity inventories at fire-sale prices—and worldwide prices hit bottom. During these decades of depleting supply, demand for commodities continued to grow.

Asia boomed; the economies of the West and the rest of the world also grew. And, once again, Americans began consuming commodities at an expansive and carefree rate. Years of cheap oil had given drivers a taste for gas-guzzlers again. Everyone seemed to be driving SUVs that only movie stars used to own, driving fuel-economy averages to the lowest levels in 20 years.

Those new McMansions rising around the nation, thanks to record-low mortgage rates, required lots of heating and cooling. Big cars and houses also eat up huge supplies of lumber, steel, aluminum, platinum, palladium, and lead for vehicle batteries. Europeans, too, were experiencing a housing boom and driving more and bigger cars than ever, including SUVs.

Natural gas, cleaner and more efficient than oil or coal, had become the fuel of choice for North American power plants. Demand in the energy and industrial metals sectors increased further with the widespread economic recovery in Asia. South Korea has become one of the world's leading importers of commodities. Short of scrap, Japan is racking up record imports of refined copper.

And then there was China, gobbling up commodities like the giant economic dragon it was destined to be.

All this demand has come at a time when China is short of virtually every raw material it needs. Nor are its neighbors in any position to chip in. With few homegrown commodities of their own, South Korea and Japan are now competing with China for raw materials.

In fact, most of Asia has grown dramatically over the past 25 years, pushing up demand further. India's economy, too, has been growing at its most rapid rate in 15 years, supposedly expanding more than 8 percent between March 2003 and March 2004—which would make it the second-fastest-growing economy in the world after China—and thus increasing its demand for goods. And while Russia may have vast deposits of oil and minerals, the country is falling apart economically as privateers and mafia capitalists strip their nation's assets, undercutting world supply and further hiking prices.

Ironically, U.S. investors were too distracted by their own booming economy and stock market in the 1990s to invest any money in increasing productive capacity of raw materials, agricultural products, and other hard assets.

And thus the seeds of the current commodities bull market were sown throughout the world: exploding demand for commodities at the very time that supplies were becoming depleted and investment in the natural resources infrastructure was virtually nonexistent.

With that kind of supply-and-demand imbalance, prices can go in only one direction, and that's up.

Good investing,

Jim Rogers

From Hot Commodities

Editor's Note: Jim Rogers has been described as "the Indiana Jones of finance."

He's been around the world on a motorcycle. He founded one of the greatest performing hedge funds in history with George Soros, he's taught finance at Columbia University's business school and he's written three classic books on investing. He lives in New York City with his wife, Paige Parker, and their daughter, who is learning Chinese and owns commodities but doesn't own stocks or bonds.

The essay you just read was taken from Jim's recently released book, Hot Commodities: How Anyone Can Invest Profitably in the World's Best Market.You can order a copy here: Hot Commodities.

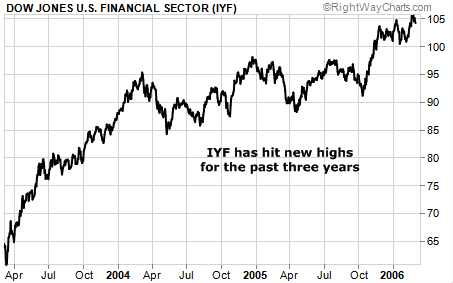

Market NotesA BRISK BUSINESS IN THE MONEY GAME In Wednesday's Market Notes section, we highlighted how "the market" is in disagreement with the large financial media crowd claiming America's financial system is about to disintegrate.

The crowd claims we have no money left to spend... that financial Armageddon is around the corner... etc. While we realize U.S. has real long-term money problems, we must listen to the market for now. The market is saying the finances of America are just fine.

The market in this case is the price action of the iShares Dow Jones U.S. Financial Sector Index Fund (IYF). This exchange-traded fund (ETF) is made up of financial titans like Citigroup (C), JP Morgan (JPM), Morgan Stanley (MS), and American Express (AXP).

These are the companies that benefit when loans are paid back, when businesses expand, and when stocks and bonds are purchased. As the chart below shows, the big boys of finance are doing brisk business as a whole... and rising stock prices reflect the good times.

Until this security makes a meaningful breakdown, let's be done with the "America is bankrupt" stuff and move on.

|

Recent Articles

|