| Home | About Us | Resources | Archive | Free Reports | Market Window |

|

Editor's note: Last month, Porter Stansberry wrote a series of educational essays that "distilled" the wisdom he has acquired over his 20-year investment career. Porter's series was a huge hit with readers. Today, we're passing along one of the best ideas he shared…

The Only Investments I Hope My Kids Ever MakeBy

Friday, July 11, 2014

I have a very simple question for you...

If you were going to limit all of your investments to only one sector of the economy – only one type of business or one kind of stock – what would you buy?

We've come to believe that, for outside and passive investors (common shareholders), there are very few sectors that offer truly extraordinary rates of return and that don't require taking any material risk. Let me be clear about what I mean. There are only a few sectors of the economy where companies can establish and maintain a truly lasting competitive advantage and outside investors can identify attractive values.

As I teach my children about investing, I will focus almost entirely on examples from these sectors. And truly... I will spend most of my time explaining only one business to my children.

If they come to understand this business thoroughly, I know, with a reasonable amount of saving discipline, they will be financially secure by the time they are 30 years old... and wealthy long before they reach 50.

In today's essay, I'm going to explain what we see in this sector of the stock market. I want to show you why the investment returns are so incredibly good over the long term. I want you to know how to think about these businesses... how they work... and know a few simple keys to making great investments in this sector.

I promise... this is all far easier than you're imagining right now. And I'm sure you'll want to print this essay, put it in a binder, and refer to it from time to time.

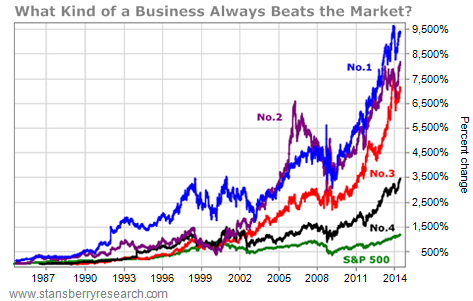

Let's start with this chart…

This chart shows four of the best-managed insurance companies in the United States. Company No. 1 got its start insuring contact lenses and now it mostly insures things that other companies won't touch, like oil rigs and summer camps. It's a pretty small public company, worth about $2 billion.

Company No. 2 was founded by a Harvard graduate just out of college about 40 years ago. It is still mostly a family business (even though it has public shareholders and is worth $6 billion). It insures almost anything commercial, from yachts to elevators.

Company No. 3 is one of the world's largest insurance companies. It insures everything – homes, cars, boats, weddings (yes, weddings), etc. It is worth $33 billion.

And Company No. 4 is a major global company that (again) insures virtually anything and is worth $22 billion.

You might think, outside of being in the insurance industry, these companies have almost nothing in common. Some are very small and insure essentially niche items. Others are huge, operate globally, and insure virtually anything. Yet to us, these companies look nearly the same: They are among the very best underwriters in the world.

That means these insurance companies almost always demand more in insurance premiums than they will end up spending on insurance claims. As you will soon learn, there's probably nothing more valuable in the financial world than having the skill and the discipline to underwrite insurance profitably.

Over the long term, all of these companies have generated returns that are more than double the S&P 500. They did so without taking any risk – something I'll explain more fully below. And... here's the best part... their success was both inevitable and repeatable. These are not "lucky guesses" or fad-driven product sales.

One of our overriding goals at Stansberry & Associates Investment Research is to give you the knowledge we'd want to have if our roles were reversed. Knowing what I know now about finance, I wouldn't have gotten into the investment newsletter business. I would have gotten into insurance.

There is nothing more valuable we can teach you than understanding how to invest in good insurance companies. And with the legwork we do in our Insurance Value Monitor (a part of our Stansberry Data service), it's as easy as pointing and clicking. If a company passes our tests and you can buy it at the right price... you can be next to 100% sure that the investment will produce outstanding returns. It's like painting by numbers. Only it will make you rich.

Let me say it one more time... I believe if individuals would limit themselves to only investing in insurance companies – and no other sector – they would greatly increase their average annual returns. We don't believe that's true of any other sector of the market.

There's a simple reason for this. If you'll think about it for a minute, it should become intuitive. Here's why insurance is the world's best business: Insurance is the only business in the world that enjoys a positive cost of capital.

In every other business, companies must pay for capital. They borrow through loans. They raise equity (and must pay dividends). They pay depositors. Everywhere else you look, in every other sector, in every other type of business, the cost of capital is one of the primary business considerations. Often, it's the dominant consideration. But a well-run insurance company will routinely not only get all the capital it needs for free, it will actually be paid to accept it.

I want to make sure you understand this point. All of the people who make their living providing financial services – banks, brokers, hedge-fund managers, etc. – all of them pay for the capital they use to earn a living. Banks borrow from depositors, investors who buy CDs, and other banks. They have to pay interest for that capital. Likewise, virtually every actor in the financial-services food chain must pay for the right to use capital. Everyone, that is, except insurance companies.

Now just follow me here for a second... Insurance companies take the premiums they've collected and they invest that capital in a range of financial assets. Assume, just for the sake of argument, that they earn 10% each year on their premiums. (That is, they make 10% on their underwriting.) And assume they invest only in the S&P 500… What do you think the average return on their assets will be each year? In this hypothetical example, their return would be 10% plus whatever the S&P 500 returned.

In reality, of course, few insurance companies can make such a large underwriting return. And few insurance companies invest a large percentage of their portfolio in stocks. Most stick to fixed income to make sure they can always pay claims. But the point remains valid. By compounding underwriting profits over time, year after year, into the financial markets, insurance companies can produce very high returns.

And here's the best part: Insurance companies don't really own most of the money they're investing. They invest the "float" they hold on behalf of their policyholders. Float is the money they've received in premiums, but haven't paid out yet. Underwritten appropriately, this is a risk-free way to leverage their investments and can result in astronomical returns on equity over time.

Just look at insurance company No. 1 in the chart above. It has produced eight times the S&P 500's long-term return. Can you think of any investor, anywhere, who has done anything like that? There isn't one. That kind of performance was only possible because, using a small equity base, the firm has invested profitably underwritten float into solid investments, year after year.

Do you like paying taxes? Well, you won't like insurance stocks, then. They have huge tax advantages. Insurance is, far and away, the most tax-privileged industry in the world. Many of their investment products are totally protected from taxes. And their earnings are sheltered, too. Insurance companies don't have to pay taxes on the cash flow they receive through premiums because, on paper, they haven't technically earned any of that money. It's not until all of the possible claims on the capital have expired that the money is "earned."

So unlike most companies that have to pay taxes on revenue and profits before investing capital, insurance companies get to invest all of the money first. This is a stupendous advantage. It's like being able to invest all of the money in your paycheck – without any taxes coming out – and then paying your tax bill 10 years from now.

I realize that I can't make you (or anyone else) actually invest in insurance stocks. And I know that no matter what I say, most of you – probably more than 90% – never will. It's a tough industry to understand, filled with financial concepts and tons of jargon. But there are two reasons the smartest guys in finance wind up in insurance, one way or another...

First, it pays the best. And second, it takes real genius to understand. But... my goal is to make it so easy to understand and follow that any reasonably diligent subscriber can do so. I'd urge you to read the March 2012 issue of my Investment Advisory newsletter for more details about how we analyze insurance stocks.

In the meantime, I want to simply show you the one number you've got to know to invest safely and successfully.

Normal measures of valuation don't apply to insurance companies. Why not? Because regular accounting considers the "float" an insurance company holds as a liability. And technically, of course, it is. Sooner or later, most (but not all) of that float will go out the door to cover claims. But because more premiums are always coming in the door, float tends to grow over time, not shrink. So in this way, in real life, float can be an important asset – by far the most valuable thing an insurance company owns. But there's one important catch...

Float is only valuable if the company can produce an underwriting profit. If it can't, float can turn into a very expensive liability.

That's why the ability to consistently underwrite at a profit is the key – the whole key – to understanding which insurance stocks to own. Outside of underwriting discipline, almost nothing differentiates insurance companies. And they have no other way to gain a competitive advantage. Warren Buffett – who built his fortune at Berkshire Hathaway largely on the backs of profitable insurance companies – explained this in his 1977 shareholder letter:

Thus, the basis of competition between insurance companies is underwriting. That is... to be successful, insurance companies must develop the ability to accurately forecast and price risk. And they must maintain their underwriting discipline even during "soft" periods in the insurance market when premiums fall. In our Insurance Value Monitor, we track nearly every major property and casualty insurance company in the U.S. and in Bermuda (where many operate to avoid U.S. corporate taxes completely). We rank every firm by long-term underwriting discipline. We've done the legwork for you. All you have to do is know what price to pay. So if normal accounting doesn't apply for insurance stocks, how do you value them? Again, we went to the master, Warren Buffett, to see what he was willing to pay for very well-run insurance companies.

Bryan Beach, our lead insurance analyst, found data on three of Buffett's biggest insurance purchases. In 1998, he bought General Re for $21 billion, which added $15.2 billion to Berkshire's float and $8 billion in additional book value. So Buffett paid $0.94 for every dollar of float and book value.

Before that, in 1995, Buffett bought 49% of GEICO for $2.3 billion, which added $3 billion to Berkshire's float and $750 million in additional book value. So Buffett paid $0.61 for every dollar of float and book value.

And way back in 1967, Buffett paid $9 million for $17 million worth of National Indemnity float. That's $0.51 for every dollar of float. Looking at these numbers, we expect to pay something between $0.75 and $1 for every dollar of float and book value.

In short, there are two fundamental rules to investing in insurance stocks. Rule No. 1: Make sure the company earns an underwriting profit almost every year, no exceptions. And Rule No. 2: Never pay more than 75% of book value plus float.

If you follow these simple rules, there's no reason you can't make large, consistent gains in the stock market... while taking little risk.

Regards,

Porter Stansberry

Further Reading:

Insurance companies aren't the only great compounding machines in the stock market. In January, Porter shared another type of business that individual investors should focus on. "These companies all produce something akin to financial anti-gravity: They earn more and more money, year after year," he writes. Read the full story here.

Market NotesTHE BOTTOM IS STILL IN FOR GOLD Another month goes by... and gold continues to hold above the $1,250 level. It's a good sign for gold owners.

Longtime readers know that when we started publishing DailyWealth in 2005, we were outspoken bulls on gold. (We were gold owners and gold bulls years before that.) Since then, we've published hundreds of essays on the right ways to own it. We even published a book on the stuff.

In 2013, gold dropped from $1,700 per ounce to $1,200 an ounce. Since then, gold sellers have tried to push it below the $1,200 area several times... only to meet up with strong buying pressure. This is the area where large buyers like Asian central banks are stepping in to buy gold.

Last month, we noted the $1,200 – $1,250 area was a "hard floor" for the metal. As you can see from the chart below, gold continues to hold this level. The bottom is still in for gold.

|

Recent Articles

|