| Home | About Us | Resources | Archive | Free Reports | Market Window |

|

Editor's note: We're continuing our series from New York Times bestselling author Bill Bonner. All week, we're featuring excerpts from his latest book... Yesterday, he argued that most of the math used by modern economists is "fishy" if not downright fraudulent. Today, we're taking a closer look at the math used to calculate one of the most widely followed numbers in the country: the inflation rate. Here's Exactly How the Government Manipulates Inflation RatesBy

Tuesday, July 29, 2014

Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, president of Argentina, will never be remembered as a great economist.

Nor will she win any awards for "accuracy in government reporting."

Au contraire: under her leadership, the numbers used by government economists in Argentina have parted company with reality completely. They are not even on speaking terms.

Still, Ms. Fernandez deserves credit. At least she is honest about it.

The Argentine president visited the U.S. in the autumn of 2012. She was invited to speak at Harvard and Georgetown universities. Students took advantage of the opportunity to ask her some questions, notably about the funny numbers Argentina uses to report its inflation.

Her bureaucrats put the consumer price index (CPI) – the rate at which prices increase – at less than 10%. Independent analysts and housewives know it is a lie. Prices are rising at about 25% per year.

At a press conference, Cristina turned the tables on her accusers: "Really, do you think consumer prices are only going up at a 2% rate in the U.S.?"

Two percent was the number given for consumer price inflation by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) in 2012. But in North America as in South America, the quantitative analysts (quants) work over the numbers as if they were prisoners at Guantanamo. Cristina is right. The numbers all wear orange jumpsuits. The Feds are the guards. Waterboard them a few times, and the numbers will tell you anything you want to hear.

The "inflation" number is probably the most important number the number crunchers crunch, because it crunches up against most of the other numbers, too. If you say your house went up in price, we need to know how much everything else went up in price, too. If your house doubled in price while everything else roughly doubled too, you realized no gain whatsoever. Likewise, your salary may be rising; but it won't do you any good unless it is going up more than the things you buy. Otherwise, you're only staying even, or maybe slipping behind.

GDP growth itself is adjusted by the inflation number. If output increases by 10%, yet the CPI is also going up at a 10% rate, real output, after inflation, is flattened out. In pensions, taxes, insurance, and contracts, the CPI number is used to correct distortions caused by inflation.

But if the CPI number is itself distorted, then the whole shebang gets twisted.

You may think it is a simple matter to measure the rate of price increases. Just take a basket of goods and services. Follow the prices. Trouble is, the stuff in the basket tends to change. You may buy strawberries in June, because they are available and reasonably cheap. Buy them the following March, on the other hand, and they'll be more expensive. You will be tempted to say that prices are rising.

The number crunchers get around this problem in two ways. First, they make "seasonal adjustments" in order to keep prices more constant. Second, they make substitutions; when one thing becomes expensive, shoppers switch to other things. The quants insist that they substitute other items of the same quality, just to keep the measurement straight. But that introduces a new wrinkle.

Let us say you need to buy a new computer. You go to the store. You find that the computer on offer is about the same price as the one you bought last year. No CPI increase there! But you look more closely and you find that this computer is twice as powerful. Hmmm. Now you are getting twice as much computer for the same price. You don't really need twice as much computer power. But you can't buy half a computer. So, you reach in your pocket and pay as much as last year.

What do the number guards do with that information? They maintain that the price of computing power has been cut in half! They can prove that this is so by looking at prices for used computers. Your computer, put on the market, would fetch only half as much as the new model. Ergo, the new model is twice as good.

This reasoning does not seem altogether unreasonable. But a $1,000 computer is a substantial part of most household budgets. And this "hedonic" adjustment of prices exerts a large pull downward on the measurement of consumer prices, even though the typical household lays out almost exactly as much one year as it did the last. The typical family's cost of living remains unchanged, but the BLS maintains that it is spending less.

You can see how this approach might work for other things. An automobile, for example. If the auto companies began making their cars twice as fast, and doubling the prices accordingly, the statisticians would have to ignore the sticker prices and conclude that prices had not changed.

Or suppose a woman buys a new pair of shoes for $100. She never wears them, so a year later, she tries to sell them back to the store. The store refuses, saying they are out of style. So, she goes to a used clothing store and sells them for only $5 – a 95% drop. Does that mean a new pair of shoes is 20 times better? If that is so, assuming she buys another pair for $100, has she really got a $2,000 pair of shoes?

Hedonics, seasonal adjustments, substitutions – the quants can trick up any number they want.

BLS will give you a precise number for the CPI, as though it had a specific, exact meaning. But all the numbers are squishy. Nothing is stiff and dry. Not a single statistic can be trusted. Yet economists build with them as though they were bricks.

A flapping cod is piled on a slippery trout on which is placed a slithering eel. And upon this squirming, shimmying mound, they erect their central planning policies.

– Adapted from Hormegeddon: How Too Much of a Good Thing Leads To Disaster. Copyright © 2014 by Bill Bonner.

Further Reading:

"Investors are terrified of inflation right now," Steve Sjuggerud writes. "But is it really a worry? It is poised to eat away at your savings and wreck your income investments?" Find out what the facts say about inflation right here.

Steve says it's so easy for a government to create inflation that nobody believes that DEFLATION – the opposite of inflation – is possible. "But it is," he writes. And it "could trigger a financial storm that nobody is expecting." Get all the details here.

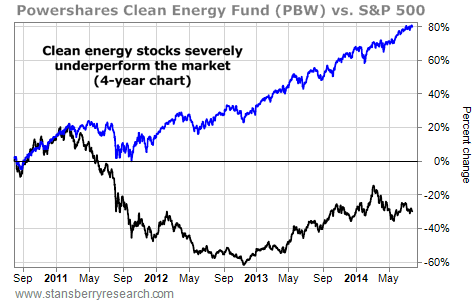

Market NotesAS EXPECTED, CLEAN ENERGY DISAPPOINTS Clean energy stocks have been losers over the past three years. Regular DailyWealth readers aren't surprised...

Over the years, we've heaped a lot of abuse on the idea of investing in clean energy companies. Most of these firms have such terrible business models that we say they are "perfectly hedged." They are able to lose money in both good times and bad. Their stocks are able to sink in both bull and bear markets. For example, the darling of the sector, solar energy, has a problem called "night."

A good way to track the clean energy sector is with the PowerShares Clean Energy Fund (PBW). It's a "one click" way to buy a basket of clean energy firms, like solar and wind power companies.

The chart below plots the performance of PBW (black line) vs. the benchmark S&P 500 index (blue line) over the past four years. As you can see, the broad market has soared (about 80%), while clean energy has declined (about 20%). Don't say we didn't warn you!

|

Recent Articles

|