| Home | About Us | Resources | Archive | Free Reports | Market Window |

|

Editor's note: We're continuing our series from New York Times bestselling author Bill Bonner. All week, we're featuring excerpts from his latest book... Yesterday, he explained how the government uses "fishy" numbers to manipulate inflation, tax rates, Social Security payments, bond prices, and the definition of "poverty." Today, he'll show you why one of the most widely reported economic benchmarks means next to nothing...

Don't Be Fooled By Friday's Unemployment ReportBy

Thursday, July 31, 2014

The Bureau of Labor Statistics said, in the spring of 2013, that 7.8% of the workforce was unemployed.

Simple enough.

But what does that mean? What is the "workforce"? And what does it mean to be "unemployed"?

Think of all those people who work for cash – the immigrant laborers waiting at gas stations and Home Depot for day work, the college students who babysit and tutor your children, everyone selling stuff on Craigslist or eBay. Are they unemployed? How about the guy who couldn't find a job, so he went back to school? Is he unemployed? What about the housewife who would like to find a job but isn't actively looking for one?

Are these people part of the workforce?

It's obvious that you can change the assumptions a bit and change the reported unemployment rate a lot.

When statistician John Williams looks at the U.S. data, for example, and applies the same formula for determining unemployment rates as was used up until the early 1990s, he comes up with a real unemployment rate of 23% – almost as high as the jobless rate in Spain.

And yet, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics told us in early 2013 that American unemployment was 7.8%. Not "around 7%." Not "less than one in 10." But 7.8% exactly.

The precise number pretends to tell you something, but once you have taken it in, you know less than you did before, because what you think you know is largely a fraud. You have more information and less knowledge.

That is the declining marginal utility of numbers, of economics.

The exact number of people who want a job and can't get one is immeasurable and unknowable. It is unknowable because people aren't stick figures. There is no average man who is either working or not working. Each person's situation is different, and often the person himself doesn't know whether or not he is jobless.

I saw a bum on the street in Baltimore the other day. He stopped me and asked if I could spare a dollar. I said I couldn't give him a dollar. "Free money could adversely affect your moral character development," I explained.

Instead, I offered him a job. I had some work to do around the office; I thought I was doing him a favor. What do you think he said?

It begins with an "F."

Should that man be counted as unemployed? He certainly didn't have a job. But if you offer a job to most people, what will they say? Maybe. Because their answer depends on a lot of questions that even they don't have the answers to. How much will they be paid? How many holidays will they have? How far will they have to commute? Will they get health benefits? How much do they really want to work? How much responsibility are they really willing to take?

And those are just the obvious questions. If you're considering taking a job, you also have to think: "What are my other options? Could I make more without working? Maybe I should start my own business instead. Let me see if I can get on disability first..."

That's why the old economists thought it was absurd to try to calculate an unemployment rate. It was just an empty number. And it was even more absurd to try to "increase" employment; you might as well try to increase the sale of pumpkins. As long as buyers and sellers of labor were both free to make deals, there would never be any "unemployment" problem, or any pumpkin problem. There would merely be people who, given the current bid, decided to withhold their labor from the market.

The old economists knew their limits.

They could describe the conditions under which people held jobs and come up with some general rules and principles that explained why some people had jobs and others didn't; but not much more. They could not say with any precision how many people were unemployed. And they certainly had no desire to interfere with employers' and employees' private arrangements.

If people chose to work for one another, or to hire one another, it was their own business.

Modern economists, however, have a seemingly boundless, and very convenient, faith in their own abilities. Give them a number; they will make it tell the story they – or their employers – want to hear. You could take any of their numbers into protective custody and examine it. You'll find that each digit has been beaten up and dressed up to mask a bruise, a welt, a broken bone.

Today, economists tell us not only how many people are looking for work, but what to do to help them find it. How can they do that? The easy sleight-of-hand for increasing the employment rate would be to reduce the number of people in "the workforce." Fewer workers. Same number of jobs. The unemployment rate goes down.

If you're going to change the definition of "workforce," however, you have to do that when no one is looking; which is exactly what they've done. Two major changes in the way the workforce was defined in the U.S. – one in the '80s and the other in '90s – cut today's unemployment rate in half.

Or, how about this? Raise the taxes on overtime pay! This is exactly what Francois Hollande has done in France. He says it will increase employment. And maybe he's right. Because now it may be more expensive to pay someone to work overtime than it would be to hire someone new.

So, with a little luck, the unemployment numbers may look better in France. Is that good? Are people better off? Who knows? The numbers certainly don't tell you.

In America, the jobless numbers have been held down by people being lent money to go to school. So instead of people officially counted as unemployed, they are counted as in school. They load them up with debt – now more than $20,000 per graduating collegian – effectively transferring more than $1 trillion from lenders and taxpayers to the education industry. School attendance goes up. Unemployment goes down.

But is anyone better off? Economists don't know.

– Adapted from Hormegeddon: How Too Much of a Good Thing Leads to Disaster. Copyright © 2014 by Bill Bonner.

Further Reading:

"We're facing the potential death of the American Dream," Steve Sjuggerud writes. "We're quickly replacing the American Dream with the European Politician's Dream – that if you're lazy and don't try hard, the government will take from those who do and give their money to you." So what can you do? Find out here.

Despite what many people believe, Porter Stansberry says our country's best days aren't behind us. "Sooner or later... the madness of our current economic policies will be so evident that this country will make wholesale changes," he writes. Learn the three ways America can get back on track here.

Market NotesTHE "PICKS AND SHOVELS" OF HEALTH CARE ARE SOARING You've heard us talk about oil services doing well... but so are medical services.

Over the years, we've told you why "picks and shovels" businesses are a great way to invest in sector booms – like the recent boom in the oil and gas business (to read our educational interview on "picks and shovels," go here).

Another booming sector is health care. With millions of Baby Boomers reaching retirement age in the U.S. each year, health care demand grows and grows. This trend has produced windfall gains for the picks and shovels of health care.

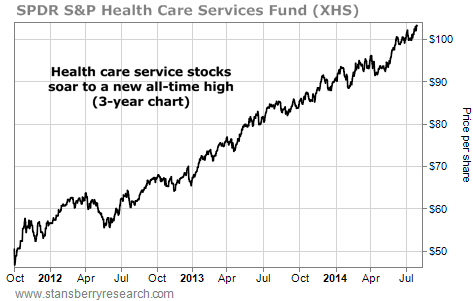

Today's chart shows the past three years' performance of the SPDR S&P Health Care Services Fund (XHS). This fund holds many companies you've probably never heard of... like top holdings BioScrip (BIOS) and Community Health Systems (CYH). But these businesses provide essential products and services ("picks and shovels") to America's hospitals, doctor's offices, and pharmacies.

As you can see, shares of XHS have been soaring. Just this week, the fund reached a new all-time high... and it has more than doubled since late 2011. It's more proof that picks and shovels investing works.

|

Recent Articles

|