| Home | About Us | Resources | Archive | Free Reports | Market Window |

|

Editor's note: We're continuing our series from New York Times bestselling author Bill Bonner. All week, we've featured essays "debunking" the economic benchmarks you see reported in the mainstream media. As Bill explained, the number crunchers "torture" those figures until they show exactly what the government wants them to show. Today, Bill takes on the biggest "flimflam" number of all...

The Real Story Behind the Latest GDP NumberBy

Friday, August 1, 2014

Are we getting richer or poorer? Are we better or worse off?

"Hey, gimme a break," says the GDP, "I just work here."

Economists can't really measure quality. So their gross domestic product (GDP) number doesn't tell us if a new house adds to the world's wealth or subtracts from it. They can only measure quantity. And speed.

An article in the Wall Street Journal explained how strong family attachments were impeding Italy's economic growth. Half the young children in Italy are raised by their grandparents – their "nonni" – while their parents work. No need for day care.

How does this affect an economy? Well, because granddad is willing to watch after little Silvio or Maria for free, the transaction doesn't register in the GDP. No exchange of money, no "growth."

The article also went on to say that people were reluctant to leave their hometowns to seek work elsewhere because they relied on the family for childcare. Theoretically, a mobile population increases GDP, too. People need to move, buy new houses and furniture, sign up for health clubs, day care and so forth.

All these things add to GDP growth. But they may do nothing to really increase quality of life. In other words, we know they add "more," but we have no idea about "better."

That is the thinking that has driven the profession of economics – and much of the world economy – to absurdity. Throughout the last 50 years, more looked so much like better, no one worried too much about the difference.

More cars. More houses. More food. More gadgets. What was not to like?

As it turns out, the concept of GDP – and GDP growth – itself wasn't just vanity, it was a deceit. It was a total fraud because the cost was more debt. And by the 21st century, the burden of debt had become so great that the system could no longer move forward.

Here is how it worked up until the early spring of 2007:

The Chinese, and others, made more stuff. The Saudis, and others, pumped more oil. Americans, and others, created more credit and used it to buy more stuff.

Rather than demand payment – in gold – for their excess dollars, as they would have before 1971, the exporters took the money and lent it back to the Americans. In this way, the U.S. never really had to settle up.

Approximately $8 trillion of purchasing power – the accumulated trade deficits between 1970 and 2007 – was created in this way. Not needing to redeem the old credits, new ones were made available to Americans. Cheap credit drove up housing prices and gave Americans the collateral to borrow more money and buy more stuff.

There is supposed to be "no such thing as a free lunch" in economics. But for years, Americans ate breakfast, lunch, and many of their dinners at someone else's expense.

When the sub-prime mortgage market collapsed in '07–'08, suddenly U.S. real estate prices stopped rising. This left millions of households in a bind. They could no longer borrow against rising home prices, because housing was going down. They had to cut back on spending, which meant less stuff could be sold to them, which left producers with bulging warehouses full of unsold goods.

Economists looked at this situation and came to the same conclusion they had on the occasion of every other slowdown over the previous 60 years. The economy needed a "stimulus" to encourage consumers to buy more stuff. They did not care that consumers might already have too much stuff, or that they were now paying the price for buying more stuff than they could afford. Nor did they wonder whether consumers' lives might be better if they focused more on quality and less on quantity.

"More" is all they know; it is all they can do, because "more" is all they can quantify. So they called for more stimulus, more debt, more credit, more spending, and more stuff.

I cut your lawn. You trim my hedges. We pay each other. The GDP goes up. The more transactions per person per year, the greater the GDP of a country.

Is anybody better off? What have the numbers really told us? Has one single extra lawn been mowed? One single extra hedge been cut down?

No. If a number – in this case, the GDP growth number – tells you that you're growing, but you're not really growing, what good is the number?

It's flimflam. An empty number. There's no good information in it. Worse, it misleads you. It has negative information content. And large public policy decisions based on it get us dangerously closer to disaster.

– Adapted from Hormegeddon: How Too Much of a Good Thing Leads to Disaster. Copyright © 2014 by Bill Bonner.

Further Reading:

Find more of Bill's insights here:

The More Precise the Number, the Bigger the Lie

"In economics, we reach the point of diminishing returns with numbers very quickly. They gradually become useless. Later... they become disastrous." Here's Exactly How the Government Manipulates Inflation Rates

"Not a single statistic can be trusted. Yet economists build with them as though they were bricks." How to Win the "War on Poverty" Without Spending an Extra Cent

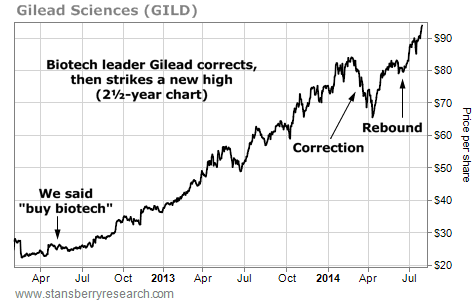

"Take the whole U.S. federal budget and divide it up. And now we have the poorest people in America with household incomes of about $55,000." Market NotesAN UPDATE ON THE BIOTECH BULL MARKET Is the biotech bull market finished? Not if you ask industry bellwether Gilead Sciences...

In 2012, we urged readers to buy the biotech sector. We like biotech because it's capable of giant booms and busts. Get into booms early, avoid the busts, and you can make great money in biotech.

Our advice was well-timed. The Nasdaq Biotech Index more than doubled in less than two years. Our preferred way to trade the sector, the leveraged biotech fund (symbol BIB), more than quadrupled in value. After such a big run, many people said the biotech bull market was due for a crash.

Shares of Gilead Sciences are a good way to gauge the action in biotech. Gilead is a giant "blue chip" in the biotech sector. When big money managers want exposure to biotech, Gilead is one of the first names they buy. It's an industry leader with strong sales growth.

As you can see from the two-year chart below, Gilead soared from mid-2012 to early 2014. Then, Gilead and the rest of the biotech sector suffered a sharp selloff. This led many to think the biotech rally was over. But Gilead has rebounded from this correction... and just struck a new high. The biotech bull market is still going.

|

Recent Articles

|