| Home | About Us | Resources | Archive | Free Reports | Market Window |

The Biggest Advantage You Have Over the 'Smart Money'By

Wednesday, March 28, 2018

Individual investors – normal people who invest their money themselves – get a bad rap...

They're usually framed as the dummies who buy from the so-called "smart money" (that is, professional investors like hedge funds, large institutional investors, and wealthy private investors).

The "smart money" has cubicle farms of frenzied MBAs crunching numbers and analyzing companies to help them make investment decisions. Individual investors have only the Internet and their wits (and newsletter providers like us, of course).

But individual investors like you and me have one huge advantage. And that's called time...

One of the big divisions in investing is between people who are focused on the "short term" – and those who invest for the "long term."

If you own an investment fund of any sort, though, those two time horizons may have a lot more in common than you'd think.

Most fund managers talk about "investing for the long term." Larry Fink, the head of BlackRock (the world's largest asset manager), wrote not long ago that his company had over time "engaged extensively with companies, clients, regulators and others on the importance of taking a long-term approach to creating value."

Of course big mutual fund companies want you to invest for the long term. After all, the longer they control your money, the more you'll pay them in fees. Their preferred holding period for your cash is forever... at 1% or 2% per year.

But many of these institutions are hiding a dirty secret about their type of "long-term" investing.

A number of years ago, I managed a hedge fund. Like most people who manage other people's money, I talked about investing for the long term.

But my idea of "long-term investing" was really "as long as the idea works." I wasn't focused on where a stock I bought was going to be trading six months, or one year, or three years later. For me, "long term" was the end of the quarter, whether that was two months, or two days, away.

And the dirty secret of most mutual funds and most other big money managers (no matter what their marketing pitches say) is that they think the same way.

Money-management companies – and the people who work for them – are usually assessed based on their quarterly performance. They have to show their holdings once every three months. And many are paid based on how they performed (compared to the index or in absolute terms) over the quarter.

Few fund managers are willing to wait for a "long-term" idea to work out if that takes more than, say, three months. Because during those three months, that's dead money. And they aren't paid a performance fee if an asset doesn't appreciate.

Of course, pretending that the short term is the long term isn't just a problem in money management. The head of BlackRock continued in his commentary:

Fortunately, as an individual investor, you have a way out of this: Invest for yourself and define your own "long term." The reality is that a stock that doesn't do anything for six months, but (say) doubles over two years is a fantastic investment... one that even great investors experience only occasionally.

Waiting can be worth it. For example, several studies have shown that buying stocks that are cheap – that is, which have low valuations – will result in better performance than buying stocks that are expensive.

One study found that over a 25-year period, the cheapest 10% of stocks in the Russell 1000 Index, a big U.S. market index, performed four percentage points better per year than the index as a whole. That means investing in the cheapest stocks would have earned you 2.5 times as much over the period than investing in the broad market.

But few fund managers have the necessary patience to hold an investment for 25 years. And they don't want to get fired – which is what happens if, as a fund manager, you sit on dead money too long.

That's why it pays to invest your own money. Maybe, like I did (and like most funds), you'll sell at the first sign of trouble. But unlike the "smart money," you can afford to give yourself time... And the best thing about giving yourself time is that it allows for good things to happen.

Good investing,

Kim Iskyan

Further Reading:

Long-term investors need to understand one thing. It's another secret that Kim learned from his fund-management days... "Every day, you are 'buying' whatever you already own," he says. Learn more here: What I Learned From a $125 Million Investment Lesson.

"Everyone has bad habits... especially when it comes to money," Kim writes. If you're ready to get closer to your financial goals, these four simple steps are a great place to start. Read more here: Start Building Your Wealth Now With These Four Financial Habits.

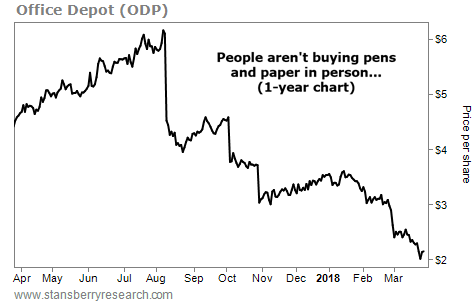

Market NotesTHE RETAIL 'SWOON' CLAIMS ANOTHER VICTIM Today's chart highlights more problems in retail...

Regular readers know that people aren't shopping the way they used to... Now, you can buy most things online and get them within a couple of days. That means brick-and-mortar retailers are losing foot traffic. We've seen this big trend with mall operator Tanger Factory Outlet Centers (SKT) and big-box retailer JC Penney (JCP). Today, we're seeing it with a company that stocks your office...

Office Depot (ODP) is one of the world's largest providers of office supplies. In the U.S., it has about 1,400 retail locations. The company sells computers, printers, paper, pens, and more – the day-to-day necessities of any office. But its business is dwindling... Office Depot's sales peaked in 2007 at more than $15 billion. At the end of last year, they were barely more than $10 billion.

As you can see below, those weak results are taking their toll. Shares are down more than 65% from their August peak, and they recently hit a new 52-week low. It's looking less and less likely that ODP will survive the retail swoon...

|

Recent Articles

|